Archaeologists have uncovered a cluster of lost cities in the Amazon rainforest that were home to at least 10,000 farmers about 2,000 years ago.

A series of earthen mounds and buried roads in Ecuador were first noticed more than two decades ago by archaeologist Stephen Rostain.

“I wasn’t sure how it all fit together,” said Mr Rostain, one of the researchers who reported on the finding in the journal Science.

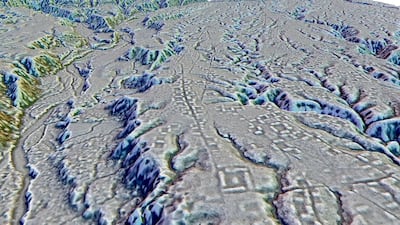

Recent mapping by laser-sensor technology revealed those sites to be part of a dense network of settlements and connecting roadways, tucked into the forested foothills of the Andes, that lasted about 1,000 years.

“It was a lost valley of cities,” said Mr Rostain, who directs investigations at France’s National Centre for Scientific Research. “It's incredible.”

The settlements were occupied by the Upano people between around 500 BC and 300 AD to 600 AD – a period roughly contemporaneous with the Roman Empire, the researchers found.

Residential and ceremonial buildings erected on more than 6,000 earthen mounds were surrounded by agricultural fields with drainage canals. The largest roads were 10 metres wide and stretched for 10km to 20km.

While it is difficult to estimate populations, the site was home to at least 10,000 inhabitants – and perhaps as many as 15,000 or 30,000 at its peak, said archaeologist Antoine Dorison, a study co-author at the French institute. That is comparable to the estimated population of Roman-era London, Britain’s largest city at the time.

“This shows a very dense occupation and an extremely complicated society,” said University of Florida archaeologist Michael Heckenberger, who was not involved in the study. “For the region, it’s really in a class of its own in terms of how early it is.”

Jose Iriarte, an archaeologist at the University of Exeter, said it would have required an elaborate system of organised labour to build the roads and thousands of earthen mounds.

“The Incas and Mayans built with stone, but people in Amazonia didn’t usually have stone available to build – they built with mud. It’s still an immense amount of labour,” said Mr Iriarte, who had no role in the research.

The Amazon is often thought of as a “pristine wilderness with only small groups of people. But recent discoveries have shown us how much more complex the past really is”, he said.

Scientists have recently also found evidence of intricate rainforest societies that predated European contact elsewhere in the Amazon, including in Bolivia and in Brazil.

“There’s always been an incredible diversity of people and settlements in the Amazon, not only one way to live,” said Mr Rostain. “We’re just learning more about them.”