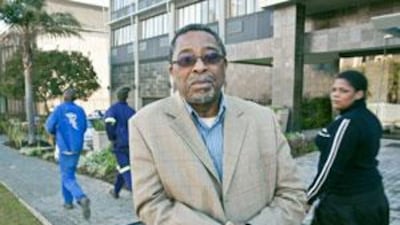

JOHANNESBURG // For the brother of a former South African president and a member of one of the country's most prominent families, Moeletsi Mbeki is a remarkably radical dissenter in Africa's political discourse. He bears a strong physical resemblance to Thabo Mbeki, six years his senior, but in his latest book, Architects of Poverty, he excoriates Africa's postcolonial political elites for failing their people.

Opening with a visit to the Slave House on the Ilé de Goree off the Senegalese capital Dakar, Mbeki writes that its back door, opening directly on to the sea and through which its human merchandise walked on to ships that would take them to a new continent never to return, has its modern equivalent in the oil rigs of the Gulf of Guinea, which extract African natural resources to be pumped directly into tankers for export around the world.

"The powerful in Africa, instead of enriching their societies, sell off the continent's assets to enrich the rest of the world," he writes. "The world has done just about everything it can to help Africa develop but there are few positive results to show for its efforts. "What has gone wrong has been the massive mismanagement by Africa's ruling political elites, with the help of western powers, of the economic surplus generated in Africa in the past 40 years."

The fundamental problem, he said in an interview in Johannesburg, is that the continent's new ruling classes are divorced from their subjects. "The black post-colonial elites have no continuity with the aristocracy that ruled Africa before, the pre-colonial elites," he said. "This means that the post-colonial elite has an identity crisis. On one hand it has no history. On the other hand it has a common grievance with the mass of the people - colonialism. Once you remove the shared grievance, there is nothing to connect it to the people.

"The old aristocracy, the feudal system, had bonds created between the ruled and the ruler. It had rules. There are no such rules in the postcolonial environment. But these people have power because they inherit a massively powerful institution which is the colonial government." Africa's independence struggles, he pointed out, were not headed by the ordinary peasant farmers who still make up the bulk of the continent's population, but were largely led by nationalists who had been part of the governing machine under colonialism and had collaborated with the colonial powers.

In the book, he cites the testimony of Macah Kunene, a businessman who was asked in 1903 by the South African Native Affairs Commission whether he wanted the British to leave the country. "If the white people and the King were to desert us now and leave us here, there is a great section of us who have approximated to a great extent the white man's way of living ? and there is a large number of us who have not advanced at all," he responded. "I am afraid that those who have remained in their former state would kill us all.

"We feel that we are far better under our [colonial] government and are far better than if we were deserted and left to the mercies of our people." His use of "our people" in the last clause is particularly telling. "The Kunene are still one of the most prominent families in South Africa, part of the new elite," Mr Mbeki said. "Because the elites have an identity crisis they have no clarity of vision and because they have no clarity of vision they are very susceptible to suggestion irrespective of where it comes from - old colonialists, capitalists in the West, communists in Russia and China."

South Africa is no exception, he added, and as a businessman himself - his roles include the chairmanship of the South African subsidiary of the Dutch television firm Endemol - as well as a commentator, he cites Black Economic Empowerment (BEE), one of the flagship policies of his brother's government, as the most telling example. Under it, he points out, politically connected black businessmen, many of them senior ANC figures such as Cyril Ramaphosa and Tokyo Sexwale, were given stakes in companies for little or no cost which have made them fortunes. Mr Mbeki argues that the scheme was driven by the old Afrikaner economic elite.

"Big companies said, 'Go on, pay yourself. We will pay the taxes but leave my company alone.' These are people who were refugees yesterday. In South Africa, with BEE, that can't give you capitalism. It gives you parasitism. "It's the same as the elites anywhere else in Africa. It has the same roots, the same identity issues and it has the same intellectual dependence." But for decades the ANC was seen as having the moral high ground, as it fought for democracy against the racism of apartheid.

"People thought they were the moral crusaders," Mr Mbeki said. "What we are now realising is the reason so much of the world supported them is they were the helpless victims in the face of the massive power of the Afrikaner. "What we thought was moral strength was actually victimhood and, as inevitably happens, the victim very quickly becomes a bully." It is an analysis that is almost brutal in its directness. The Mbeki family, though, played a key role in the struggle and its aftermath and not only through Thabo.

While Mr Mbeki was exiled in Britain where he studied at Warwick University, his father, Govan, one of the ANC's leading lights who died in 2001, spent 24 years in prison on Robben Island alongside Nelson Mandela. Effectively Mr Mbeki and his family are at the heart of the new elite he condemns so vehemently, but he cites Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin and the British Left-winger Tony Benn, the heir to the viscountcy of Stansgate, to argue that "it's normal for members of the elite to criticise their system".

As for his brother, he adds: "I'm criticising ANC policies, not him personally. The ANC is an institution. These are institutional failures." sberger@thenational.ae