The Congress party’s election manifesto, released on Tuesday, promises more government jobs, guaranteed incomes for the poor, farm loan waivers, more funding for education, and lower corporate tax rates. But the manifesto does not reveal any ideas about how India will pay for all of these plans.

Voting for India’s national election in seven phases begins on April 11, and the Congress is positioning itself as the progressive champion of India’s poor and unemployed. Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party have, the Congress insists, let the economy down.

The BJP has yet to release its own manifesto, but Arun Jaitley, India’s finance minister, called the Congress’ manifesto “dangerous and un-implementable”.

In its 54-page manifesto, the Congress vows support for a number of causes dear to India’s liberals. These include the removal of a centuries-old sedition law; amending an act that offers soldiers legal immunity for crimes committed in troubled parts of the country; protecting digital privacy rights; a focus on environmental conservation; and strengthening the laws against hate crimes that target minorities.

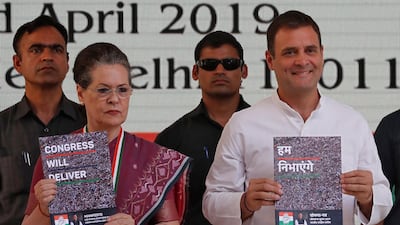

The majority of the party’s economic platform is premised on what it views as Mr Modi’s failures. “The economy is jammed,” Rahul Gandhi, the Congress president, said at the launch of the manifesto.

Notably, India's unemployment rate stands at around 6 per cent – a figure that was leaked to the Business Standard newspaper but that is otherwise difficult to verify, since Mr Modi's government has withheld data on jobs. The joblessness rate, as leaked, is the highest in 45 years.

Praveen Chakravarty, the Congress’ chief data scientist, told Reuters that his party could bring unemployment down to 3 or 4 per cent over five years.

Part of this effort involves filling 2.2 million government jobs across the country that remain vacant. The Congress also plans to create another 1 million jobs in local government bodies, and to offer incentives to businesses that generate employment.

In a bid to alleviate poverty, the Congress has outlined a scheme to provide an annual basic income of 72,000 rupees ($1,040) to the poorest fifth of Indian households. Roughly 50 million households will qualify for this income, translating into an expenditure of 3.6 trillion rupees – roughly $52.2 billion, or two per cent of the Indian GDP.

“The scheme is an implicit acknowledgement that market reforms haven’t helped the poorest of the poor,” said John Samuel Raja, the founder of How India Lives, a firm that analyses public data. “It’s an acknowledgement that the state hasn’t found the ability to serve the needs of these people.”

Additionally, Mr Gandhi has said that his party will raise spending on education to 6 per cent of the GDP, up from 2.7 per cent now. The manifesto mentions a loan waiver to farmers, although it does not specify which farmers will qualify. It also promises lower direct tax rates on companies, and lower corporate and income tax on tourism-related income.

These are expensive propositions, especially for a country that has recently seen its fiscal deficit rise. Over the past week, Indian newspapers reported, from an analysis of government data, that tax collections have slowed. For the period from April 2018 to February 2019, according to the data, the deficit had overshot the fiscal year target of 6.2 trillion rupees, or $90.5 billion, by 34 per cent.

Mr Modi’s government is trying to keep its fiscal deficit – the difference between its revenue and its expenditure – at 3.3 per cent of GDP in the current fiscal year.

The Congress has been scathing about the projected deficit, and about Mr Modi’s handling of the economy in general. On Saturday, Randeep Surjewala, a party spokesperson, called “Modinomics” a “flop”.

But the Congress itself has not been clear about how it will fund the schemes laid out in its manifesto.

On Tuesday, Mr Chakravarty wrote a column in the Economic Times newspaper, claiming that "fiscal prudence" was key to the Congress' basic income project. Most of it would be financed by "a combination of increased revenues and expenditure rationalisation", he wrote. Existing welfare schemes, which dispense food, fuel, health and employment to the poorest of India's poor, need not be cut, he added.

But neither Mr Chakravarty nor the Congress manifesto have spelled out how they plan to increase revenues and streamline expenses. “It is impossible at this manifesto stage to detail out an entire Budget proposal,” Mr Chakravarty wrote.

Mr Raja said that the government will be able to finance these plans if economic growth picks up once more.

“To me, the Congress’ calculations will depend on how the economy grows, and that in turn will depend on how businesses respond with new investment,” Mr Raja said. “It’s all linked to that. You have to make the engine start running again, and that’s where the BJP has really failed.”