A remote-controlled underwater vehicle is now helping divers search for the remains of victims and flight recorders from a Sriwijaya Air jet that crashed into the Indonesian sea three days ago shortly after take-off.

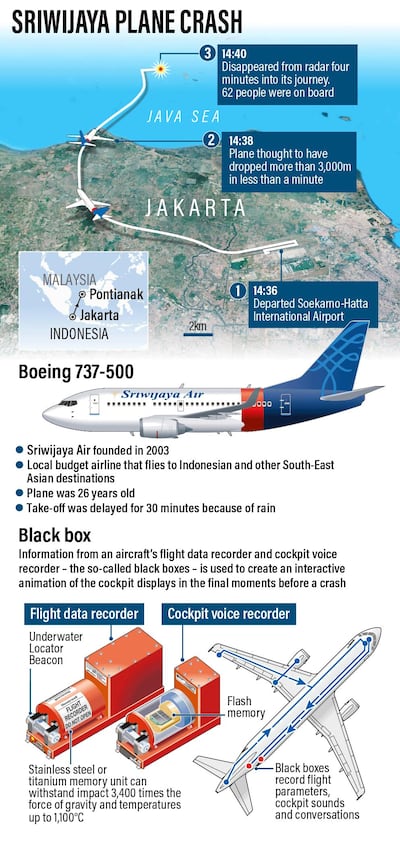

The Boeing 737-500 plane with 62 people on board plunged into the Java Sea on Saturday afternoon, four minutes after taking off from Jakarta’s main airport.

Indonesian police made the first identification of a victim from the crash on Monday. Flight attendant Okky Bisma was identified by his fingerprints, said a police official.

“My super kind husband ... Heaven is your place ... Until we meet again darling,” Okky’s wife, who is also a flight attendant, wrote on her Instagram account.

The Boeing 737-500 jet was headed on a domestic flight to Pontianak on Borneo island, about 740km from Jakarta, before it disappeared from radar screens.

It was the second major air crash in Indonesia since 189 passengers and crew were killed in 2018 when a Lion Air Boeing 737 MAX also plunged into the Java Sea soon after taking off. The jet that crashed on Saturday is a different design.

“Today we are focusing on finding the victims,” Yusuf Latif, a spokesman for search and rescue agency Basarnas, said on Tuesday.

Divers have narrowed down an area where they believe the flight recorders, known as black boxes, are believed to be but search efforts have been hindered by debris, officials said.

The remotely operated underwater vehicle has been deployed to help scour the seabed, while navy vessels with sonar search from the surface.

Once the flight data and cockpit voice recorders are found, Indonesia’s National Transportation Safety Committee (KNKT) expects to be able to read the information in three days.

With few immediate clues on what caused a catastrophic loss of control after take-off, investigators will rely heavily on the flight recorders to determine what went wrong.

The Sriwijaya Air plane was nearly 27 years old, much older than Boeing’s problem-plagued 737 MAX model.

Older 737 models are widely flown and do not have the stall-prevention system implicated in the MAX safety crisis.

Starting with just one plane in 2003, Sriwijaya Air has become Indonesia’s number 3 airline group, aided by its strategy of acquiring old planes at cheap prices and serving routes neglected by competitors.

The mid-market airline, which has few international flights was launched by brothers Chandra and Hendry Lie, whose family was involved in tin mining and the garment industry, and their business partners 17 years ago. Their single plane flew from their home town of Pangkal Pinang on Bangka Island to Indonesia's capital Jakarta.

Its focus on second and third-tier routes gave it a loyal customer base and helped it snare nearly 10 per cent market share behind Lion Air and national carrier Garuda Indonesia.

"They had a reasonable business approach," an industry source who was not authorised to speak publicly said of Sriwijaya's founders.

"They are not flamboyant people like many you see running airlines."

They used a conservative business model of acquiring older planes on the cheap rather than taking advantage of low-cost financing to purchase large fleets of new aircraft like other fast-growing carriers such as Lion Air, Malaysia's AirAsia Group Bhd and Vietnam's VietJet Aviation JSC.

The fleet of Sriwijaya and regional offshoot NAM Air is nearly 20 years old on average – nearly three times older than Lion Air group, according to website Planespotters.net.

The plane involved in the crash, a 737-500, was one of only 77 remaining in service globally, aviation data provider Cirium said. Other current operators including the likes of Nigeria's Air Peace and Kazakhstan's SCAT Airlines.

Two former Sriwijaya employees told Reuters there were strategic reasons for keeping such an old model in service beyond the cheaper acquisition cost.

The smaller seating capacity of 120 was more appropriate for certain routes like Jakarta to Pontianak on Borneo flown by the plane that crashed on Saturday and the 737-500 could land at airports that were otherwise served by turboprops due to short runway lengths, they said on condition of anonymity.

Sriwijaya did not respond immediately to a request for comment.

Older jets can be operated just as safely as newer ones if maintained properly, though the cost of doing so is higher, as are the operating costs because they are less fuel-efficient.

Rising upkeep costs and low fare prices due to heated competition meant that by 2018 Sriwijaya had accrued large debts owed to Garuda's maintenance arm, GMF AeroAsia.

As of September 30, 2020, Sriwijaya and NAM owed around $63 million in unpaid bills to GMF AeroAsia and Garuda had warned of impairment losses on $37.5 million owed by Sriwijaya as part of a failed co-operation agreement, according to GMF AeroAsia and Garuda.

The status of its financial position since the start of the pandemic is unclear, but a Sriwijaya pilot, speaking on condition of anonymity, said there were salary cuts and a reduction in the number of planes operating during the pandemic, in line with many other airlines globally.

The pilot added the airline had been complying with all training and maintenance requirements throughout the pandemic.

Sriwijaya and NAM together have 34 planes for operations and half of them are in service, according to Planespotters.net.

"The question now is whether Sriwijaya, already in poor financial health, is able to overcome this accident as Covid-19 has crippled all airlines," said Shukor Yusof, head of Malaysian aviation consultancy Endau Analytics.

57%20Seconds

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDirector%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Rusty%20Cundieff%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EStars%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EJosh%20Hutcherson%2C%20Morgan%20Freeman%2C%20Greg%20Germann%2C%20Lovie%20Simone%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ERating%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E2%2F5%0D%3Cbr%3E%0D%3Cbr%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Trump v Khan

2016: Feud begins after Khan criticised Trump’s proposed Muslim travel ban to US

2017: Trump criticises Khan’s ‘no reason to be alarmed’ response to London Bridge terror attacks

2019: Trump calls Khan a “stone cold loser” before first state visit

2019: Trump tweets about “Khan’s Londonistan”, calling him “a national disgrace”

2022: Khan’s office attributes rise in Islamophobic abuse against the major to hostility stoked during Trump’s presidency

July 2025 During a golfing trip to Scotland, Trump calls Khan “a nasty person”

Sept 2025 Trump blames Khan for London’s “stabbings and the dirt and the filth”.

Dec 2025 Trump suggests migrants got Khan elected, calls him a “horrible, vicious, disgusting mayor”

Volvo ES90 Specs

Engine: Electric single motor (96kW), twin motor (106kW) and twin motor performance (106kW)

Power: 333hp, 449hp, 680hp

Torque: 480Nm, 670Nm, 870Nm

On sale: Later in 2025 or early 2026, depending on region

Price: Exact regional pricing TBA

UAE currency: the story behind the money in your pockets

Our family matters legal consultant

Name: Hassan Mohsen Elhais

Position: legal consultant with Al Rowaad Advocates and Legal Consultants.

Gulf Under 19s final

Dubai College A 50-12 Dubai College B

Ten tax points to be aware of in 2026

1. Domestic VAT refund amendments: request your refund within five years

If a business does not apply for the refund on time, they lose their credit.

2. E-invoicing in the UAE

Businesses should continue preparing for the implementation of e-invoicing in the UAE, with 2026 a preparation and transition period ahead of phased mandatory adoption.

3. More tax audits

Tax authorities are increasingly using data already available across multiple filings to identify audit risks.

4. More beneficial VAT and excise tax penalty regime

Tax disputes are expected to become more frequent and more structured, with clearer administrative objection and appeal processes. The UAE has adopted a new penalty regime for VAT and excise disputes, which now mirrors the penalty regime for corporate tax.

5. Greater emphasis on statutory audit

There is a greater need for the accuracy of financial statements. The International Financial Reporting Standards standards need to be strictly adhered to and, as a result, the quality of the audits will need to increase.

6. Further transfer pricing enforcement

Transfer pricing enforcement, which refers to the practice of establishing prices for internal transactions between related entities, is expected to broaden in scope. The UAE will shortly open the possibility to negotiate advance pricing agreements, or essentially rulings for transfer pricing purposes.

7. Limited time periods for audits

Recent amendments also introduce a default five-year limitation period for tax audits and assessments, subject to specific statutory exceptions. While the standard audit and assessment period is five years, this may be extended to up to 15 years in cases involving fraud or tax evasion.

8. Pillar 2 implementation

Many multinational groups will begin to feel the practical effect of the Domestic Minimum Top-Up Tax (DMTT), the UAE's implementation of the OECD’s global minimum tax under Pillar 2. While the rules apply for financial years starting on or after January 1, 2025, it is 2026 that marks the transition to an operational phase.

9. Reduced compliance obligations for imported goods and services

Businesses that apply the reverse-charge mechanism for VAT purposes in the UAE may benefit from reduced compliance obligations.

10. Substance and CbC reporting focus

Tax authorities are expected to continue strengthening the enforcement of economic substance and Country-by-Country (CbC) reporting frameworks. In the UAE, these regimes are increasingly being used as risk-assessment tools, providing tax authorities with a comprehensive view of multinational groups’ global footprints and enabling them to assess whether profits are aligned with real economic activity.

Contributed by Thomas Vanhee and Hend Rashwan, Aurifer

Dubai Rugby Sevens, December 5 -7

World Sevens Series Pools

A – Fiji, France, Argentina, Japan

B – United States, Australia, Scotland, Ireland

C – New Zealand, Samoa, Canada, Wales

D – South Africa, England, Spain, Kenya

Specs

Engine: 51.5kW electric motor

Range: 400km

Power: 134bhp

Torque: 175Nm

Price: From Dh98,800

Available: Now

HWJN

%3Cp%3EDirector%3A%20Yasir%20Alyasiri%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3EStarring%3A%20Baraa%20Alem%2C%20Nour%20Alkhadra%2C%20Alanoud%20Saud%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3ERating%3A%203%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Rajasthan Royals 153-5 (17.5 ov)

Delhi Daredevils 60-4 (6 ov)

Rajasthan won by 10 runs (D/L method)

Farage on Muslim Brotherhood

Nigel Farage told Reform's annual conference that the party will proscribe the Muslim Brotherhood if he becomes Prime Minister.

"We will stop dangerous organisations with links to terrorism operating in our country," he said. "Quite why we've been so gutless about this – both Labour and Conservative – I don't know.

“All across the Middle East, countries have banned and proscribed the Muslim Brotherhood as a dangerous organisation. We will do the very same.”

It is 10 years since a ground-breaking report into the Muslim Brotherhood by Sir John Jenkins.

Among the former diplomat's findings was an assessment that “the use of extreme violence in the pursuit of the perfect Islamic society” has “never been institutionally disowned” by the movement.

The prime minister at the time, David Cameron, who commissioned the report, said membership or association with the Muslim Brotherhood was a "possible indicator of extremism" but it would not be banned.

England 12-man squad for second Test

v West Indies which starts Thursday: Rory Burns, Joe Denly, Jonny Bairstow, Joe Root (captain), Jos Buttler, Ben Stokes, Moeen Ali, Ben Foakes, Sam Curran, Stuart Broad, Jimmy Anderson, Jack Leach

The bio:

Favourite holiday destination: I really enjoyed Sri Lanka and Vietnam but my dream destination is the Maldives.

Favourite food: My mum’s Chinese cooking.

Favourite film: Robocop, followed by The Terminator.

Hobbies: Off-roading, scuba diving, playing squash and going to the gym.

Which honey takes your fancy?

Al Ghaf Honey

The Al Ghaf tree is a local desert tree which bears the harsh summers with drought and high temperatures. From the rich flowers, bees that pollinate this tree can produce delicious red colour honey in June and July each year

Sidr Honey

The Sidr tree is an evergreen tree with long and strong forked branches. The blossom from this tree is called Yabyab, which provides rich food for bees to produce honey in October and November. This honey is the most expensive, but tastiest

Samar Honey

The Samar tree trunk, leaves and blossom contains Barm which is the secret of healing. You can enjoy the best types of honey from this tree every year in May and June. It is an historical witness to the life of the Emirati nation which represents the harsh desert and mountain environments

The 10 Questions

- Is there a God?

- How did it all begin?

- What is inside a black hole?

- Can we predict the future?

- Is time travel possible?

- Will we survive on Earth?

- Is there other intelligent life in the universe?

- Should we colonise space?

- Will artificial intelligence outsmart us?

- How do we shape the future?

SPEC%20SHEET%3A%20APPLE%20IPHONE%2015%20PRO%20MAX

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDisplay%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%206.7%22%20Super%20Retina%20XDR%20OLED%2C%202796%20x%201290%2C%20460ppi%2C%20120Hz%2C%202000%20nits%20max%2C%20HDR%2C%20True%20Tone%2C%20P3%2C%20always-on%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EProcessor%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20A17%20Pro%2C%206-core%20CPU%2C%206-core%20GPU%2C%2016-core%20Neural%20Engine%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EMemory%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%208GB%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ECapacity%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20256%2F512GB%20%2F%201TB%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EPlatform%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20iOS%2017%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EMain%20camera%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Triple%3A%2048MP%20main%20(f%2F1.78)%20%2B%2012MP%20ultra-wide%20(f%2F2.2)%20%2B%2012MP%205x%20telephoto%20(f%2F2.8)%3B%205x%20optical%20zoom%20in%2C%202x%20optical%20zoom%20out%3B%2010x%20optical%20zoom%20range%2C%20digital%20zoom%20up%20to%2025x%3B%20Photonic%20Engine%2C%20Deep%20Fusion%2C%20Smart%20HDR%204%2C%20Portrait%20Lighting%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EMain%20camera%20video%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%204K%20%40%2024%2F25%2F30%2F60fps%2C%20full-HD%20%40%2025%2F30%2F60fps%2C%20HD%20%40%2030fps%2C%20slo-mo%20%40%20120%2F240fps%2C%20ProRes%20(4K)%20%40%2060fps%3B%20night%2C%20time%20lapse%2C%20cinematic%2C%20action%20modes%3B%20Dolby%20Vision%2C%204K%20HDR%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EFront%20camera%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2012MP%20TrueDepth%20(f%2F1.9)%2C%20Photonic%20Engine%2C%20Deep%20Fusion%2C%20Smart%20HDR%204%2C%20Portrait%20Lighting%3B%20Animoji%2C%20Memoji%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EFront%20camera%20video%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%204K%20%40%2024%2F25%2F30%2F60fps%2C%20full-HD%20%40%2025%2F30%2F60fps%2C%20slo-mo%20%40%20120%2F240fps%2C%20ProRes%20(4K)%20%40%2030fps%3B%20night%2C%20time%20lapse%2C%20cinematic%2C%20action%20modes%3B%20Dolby%20Vision%2C%204K%20HDR%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EBattery%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%204441mAh%2C%20up%20to%2029h%20video%2C%2025h%20streaming%20video%2C%2095h%20audio%3B%20fast%20charge%20to%2050%25%20in%2030min%20(with%20at%20least%2020W%20adaptor)%3B%20MagSafe%2C%20Qi%20wireless%20charging%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EConnectivity%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Wi-Fi%2C%20Bluetooth%205.3%2C%20NFC%20(Apple%20Pay)%2C%20second-generation%20Ultra%20Wideband%20chip%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EBiometrics%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Face%20ID%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EI%2FO%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20USB-C%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDurability%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20IP68%2C%20water-resistant%20up%20to%206m%20up%20to%2030min%3B%20dust%2Fsplash-resistant%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ECards%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Dual%20eSIM%20%2F%20eSIM%20%2B%20eSIM%20(US%20models%20use%20eSIMs%20only)%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EColours%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Black%20titanium%2C%20blue%20titanium%2C%20natural%20titanium%2C%20white%20titanium%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EIn%20the%20box%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EiPhone%2015%20Pro%20Max%2C%20USB-C-to-USB-C%20woven%20cable%2C%20one%20Apple%20sticker%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EPrice%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Dh5%2C099%20%2F%20Dh5%2C949%20%2F%20Dh6%2C799%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Ziina users can donate to relief efforts in Beirut

Ziina users will be able to use the app to help relief efforts in Beirut, which has been left reeling after an August blast caused an estimated $15 billion in damage and left thousands homeless. Ziina has partnered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees to raise money for the Lebanese capital, co-founder Faisal Toukan says. “As of October 1, the UNHCR has the first certified badge on Ziina and is automatically part of user's top friends' list during this campaign. Users can now donate any amount to the Beirut relief with two clicks. The money raised will go towards rebuilding houses for the families that were impacted by the explosion.”

South Africa squad

Faf du Plessis (captain), Hashim Amla, Temba Bavuma, Quinton de Kock (wicketkeeper), Theunis de Bruyn, AB de Villiers, Dean Elgar, Heinrich Klaasen (wicketkeeper), Keshav Maharaj, Aiden Markram, Morne Morkel, Wiaan Mulder, Lungi Ngidi, Vernon Philander and Kagiso Rabada.

Our legal consultant

Name: Hassan Mohsen Elhais

Position: legal consultant with Al Rowaad Advocates and Legal Consultants.

THREE

%3Cp%3EDirector%3A%20Nayla%20Al%20Khaja%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3EStarring%3A%20Jefferson%20Hall%2C%20Faten%20Ahmed%2C%20Noura%20Alabed%2C%20Saud%20Alzarooni%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3ERating%3A%203.5%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Labour dispute

The insured employee may still file an ILOE claim even if a labour dispute is ongoing post termination, but the insurer may suspend or reject payment, until the courts resolve the dispute, especially if the reason for termination is contested. The outcome of the labour court proceedings can directly affect eligibility.

- Abdullah Ishnaneh, Partner, BSA Law

SUCCESSION%20SEASON%204%20EPISODE%201

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ECreated%20by%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EJesse%20Armstrong%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EStars%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Brian%20Cox%2C%20Jeremy%20Strong%2C%20Kieran%20Culkin%2C%20Sarah%20Snook%2C%20Nicholas%20Braun%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ERating%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%204%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

The%C2%A0specs%20

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EEngine%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E2-litre%204-cylinder%20mild%20hybrid%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETransmission%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E7-speed%20S%20tronic%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPower%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E265hp%20%2F%20195kW%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETorque%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20370Nm%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPrice%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3Efrom%20Dh260%2C000%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EOn%20sale%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20now%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

The President's Cake

Director: Hasan Hadi

Starring: Baneen Ahmad Nayyef, Waheed Thabet Khreibat, Sajad Mohamad Qasem

Rating: 4/5

THE%20SWIMMERS

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDirector%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ESally%20El-Hosaini%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EStars%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ENathalie%20Issa%2C%20Manal%20Issa%2C%20Ahmed%20Malek%20and%20Ali%20Suliman%C2%A0%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ERating%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E4%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

About Housecall

Date started: July 2020

Founders: Omar and Humaid Alzaabi

Based: Abu Dhabi

Sector: HealthTech

# of staff: 10

Funding to date: Self-funded

Tamkeen's offering

- Option 1: 70% in year 1, 50% in year 2, 30% in year 3

- Option 2: 50% across three years

- Option 3: 30% across five years