Within the wood-panelled AA Milne room of the private members' Garrick Club in London's West End, Britain’s prime minister was bouncing between old friends, delighted to be back in the company of colleagues from his journalist days.

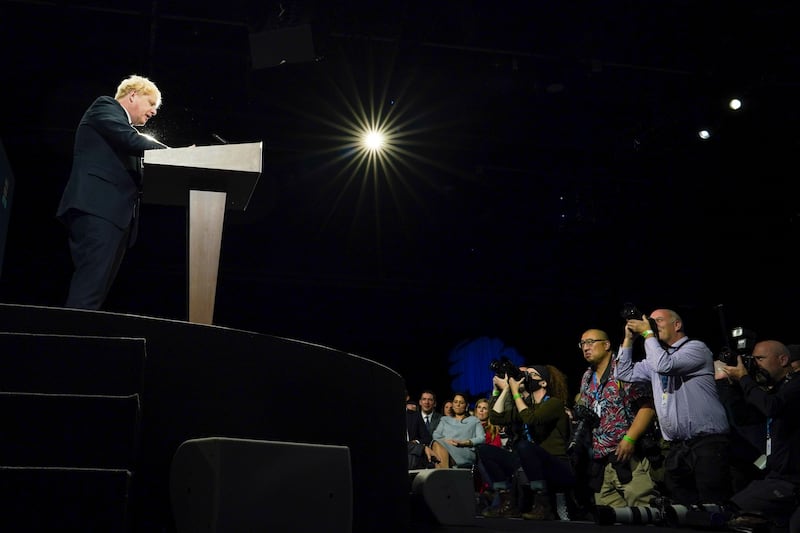

There was good reason for the spring in his step. Three weeks earlier he had set out a glorious future for Britain – following its recent departure from the EU – that had been enthusiastically embraced at the Conservative Party’s annual conference.

His lead in the polls over the opposition Labour Party looked unassailable and he had just flown down from the Cop26 climate conference in Glasgow, getting world leaders to help save the planet.

Now cocooned in the Garrick's warm grandeur, in the room named after the Winnie-the-Pooh author, for a few hours at least he could enjoy his success. And while he was not lauded by colleagues who had overlapped with his time with The Daily Telegraph, he at least enjoyed their admiration.

The evening ended with Mr Johnson skipping down the steps of the club past a press photographer waiting to snap him for a story exposing his trip from Glasgow on private jet.

It was unfortunate for Mr Johnson that within the private room of the Garrick lay the germination of a malaise – starting with the photograph – that just 10 weeks later could see him pushed out of office.

The next morning, November 3, at the Downing Street 8.30am daily meeting, it was decided to go ahead with a plan to force through legislation to ensure Conservative MP Owen Paterson was not suspended from Parliament for breaking lobbying rules.

It was a bad decision.

“That lack of basic parliamentary management is where it went wrong,” a senior former minster told The National. “Since then, it has cascaded into a whole set of other issues.”

Those “issues”, mainly the “partygate” scandal of breaking lockdown rules by having a drinks party at the prime minister's official residence at Downing Street, could prove problematic.

Strangely, much like Theresa May, the prime minister he helped to unseat, Mr Johnson does not possess many close friends within Parliament.

“The problem is that Boris doesn't really have any political allies,” said a political insider. “If you go back to [former prime ministers] [Tony] Blair and [Gordon] Brown, there were very distinct camps of people who were followers – mostly disciples who provided the political hinterland.”

That, the former minister said, could prove pivotal in whether Mr Johnson remains leader of the party. “It isn't the electorate that can finish him off at the moment it’s the parliamentary party that can.

“So, if he doesn't deal with that immediately then he's going to find himself in an increasingly toxic position. He needs to address the parliamentary party handling as something of absolute paramount importance, because if he doesn't, he’s gone.”

The politician was referring to the 54 letters of no confidence required to trigger a vote of no confidence in the leader – a move that would prove terminal.

The miscalculations in Downing Street became apparent when The National witnessed the hour-long huddle following Prime Minister’s Questions on November 3.

When the political editors of the main Tory-supporting newspapers criticised the concocted plan to absolve Mr Paterson, Downing Street officials were resolute. What they were doing was right and proper, they argued.

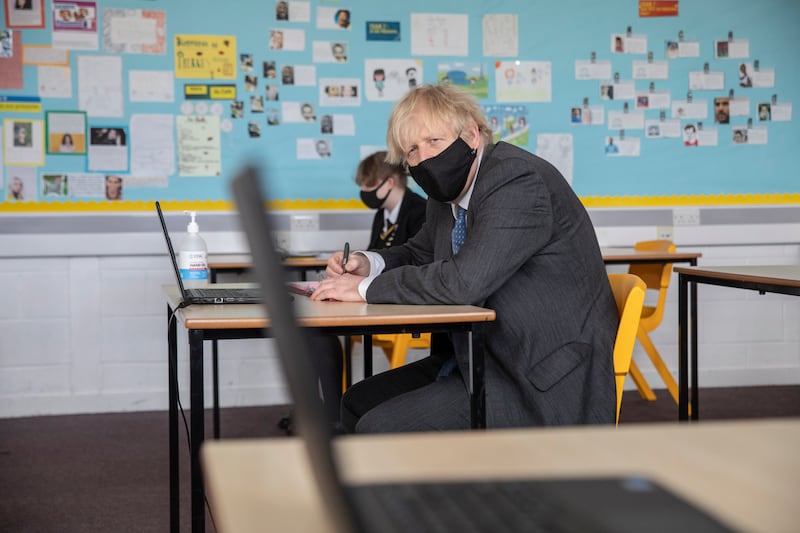

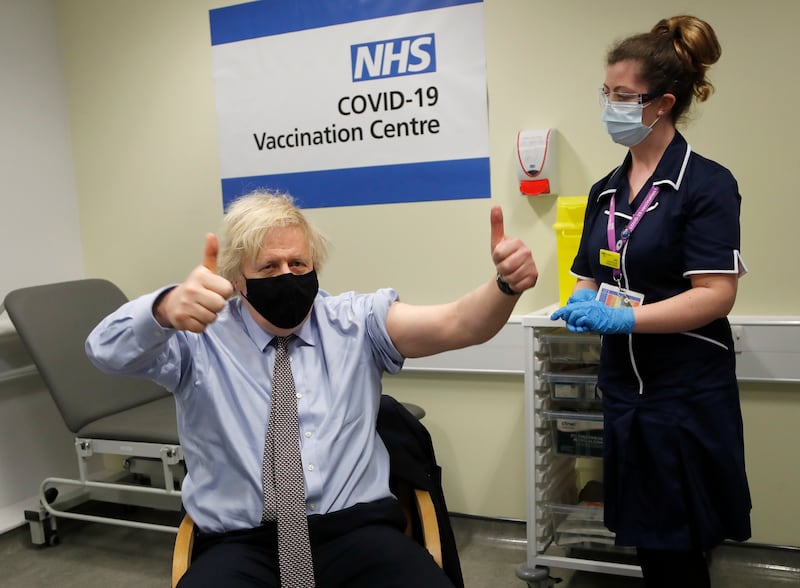

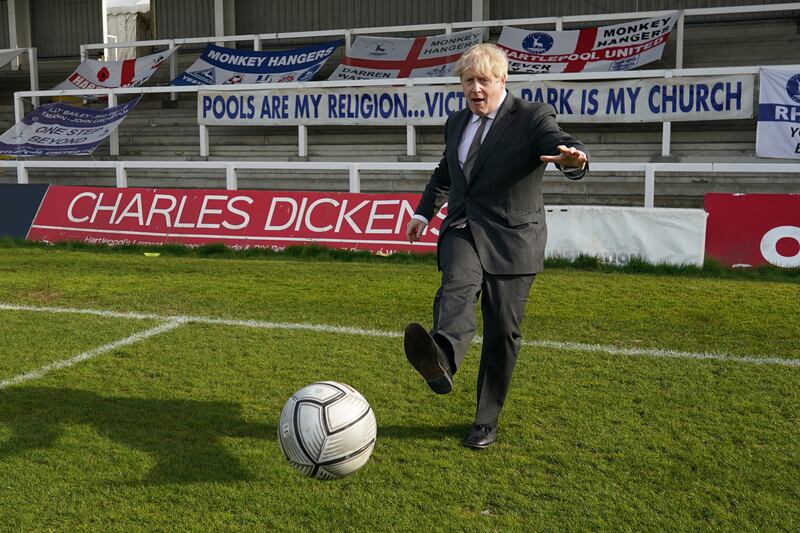

Boris Johnson's year – in pictures

Alas for Mr Johnson, the next morning’s papers contended otherwise, and a swift U-turn was performed.

But it revealed the shortcomings of the Number 10 operation, with no one telling the boss about either the incredulity of journalists or having the gumption to say pressing on with the Paterson vote was a dreadful decision.

“The prime minister wasn't well advised,” said a senior Conservative MP. “He didn't have somebody to tell him that this was completely off course, that it was the wrong judgment call.”

The rebellion over Mr Paterson and the subsequent revolt of 101 Tory MPs in the vote on new Covid-19 restrictions on 14 December shows party discipline is in disarray.

Party whips, there to ensure that MPs vote the way their leadership wants – either through persuasion, reward or coercion – are not functioning.

“The Whips' Office has clearly lost have lost the dressing room,” said one insider.

Just a few weeks ago the idea of “letters going in” would have been unthinkable, even with the Paterson business.

But Mr Johnson’s power has ebbed rapidly, so much so that MPs from the latest 2019 intake have been asking more weathered colleagues whether they should email or post their missives of no confidence.

Without doubt, it is a moment of extreme jeopardy for Mr Johnson. But so far none of his Cabinet colleagues have broken ranks and resigned – unlike the 16 Cabinet minister resignations Mrs May suffered.

But why would they? Partygate aside, the coming spring holds no cheer for the government. The National Insurance tax rise begins in April, energy prices are soaring and households face significant inflation increases.

The question remains is Mr Johnson now permanently damaged goods or will he find the right people to turn Downing Street and the Whips' Office into skilled operations?

If he does survive, in particular the partygate investigation headed by the civil servant Sue Gray, then there is a chance his fortunes could change.

“We mustn't forget that at party conference everyone thought everything was amazing, so things do swing quickly,” said the former minister.

“People tend to forget it isn't all dreadful. What’s happened is an enormous firestorm and if the prime minister survives, he has to rebuild, to change the structures within so he is best supported to deliver his programme.”

But, if it doesn’t quite work out then at least Mr Johnson knows that a hinterland of journalism, writing and the speechmaking circuit awaits that should provide an income far beyond his current salary.

There is even the knowledge that he could return to the warmth of the Garrick, to relate tales of when he ruled the land.