In the first part of his life, Abdullah Sultan Al Hebsi lived in Wadi Naqab, where he farmed wheat and chased goats in the mountains as a boy. They would visit the souq to buy rice, and sell goats, yoghurt, clarified butter and honey.

This came to an end when Al Hebsi joined the Agricultural Trials Station at the age of 15. The British project was started in 1955 to "win the hearts and minds" in the aftermath of the Buraimi incident and to introduce commercial agricultural production. Oil was yet to be discovered. It would become central to the British development programme and commercialisation efforts until 1972, when it was eventually taken over by the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries.

For Al Hebsi and his classmates in the early days, the school was their first experience of formal education, and it saw them take their first steps toward participating in an industrialised, global economy, with the opportunity for a career in government.

"I learnt everything from that school," Al Hebsi tells me. "I learnt farming; I learnt the Quran; I learnt football."

The story of the Emirates is often told through two narratives – the story of oil production, which hinges around Abu Dhabi, and the story of free trade mainly in Dubai. But the farming station is another important aspect of the country's economic and political formation.

Oil required negotiating across borders, while the commercialisation of agriculture meant looking through them and imagining integration across tribal and geographic boundaries. In this way it could be said to have laid the groundwork for federation.

And yet, the project has been all but forgotten, overtaken by political events of the age with

the formation of the nation in 1971. That is until now.

American historian Matthew MacLean has brought this very local history back into the public consciousness with his doctoral dissertation for New York University's department of history and Middle Eastern and Islamic studies.

His recently completed study, Spatial Transformations and the Emergence of 'The National': Infrastructures and the Formation of the United Arab Emirates, 1950-1980, explains the country's development process by looking at the transformation of space and infrastructure – quarries, wells, borders and the first long-distance road.

"Most of my research is about material infrastructure but it's also about how people imagine space," says MacLean. "People imagine a nation in part by locating it in a bounded territory on the map.

"Because it was a commercial economy, the agricultural station had a different imagination of what space should be and how land was used, versus the previous economy."

In the early 1950s, Britain's lack of investment in the Trucial States, as the UAE was then known, was one justification for Saudi claims on the oasis villages of the Trucial States and Oman. Buraimi marked a shift in the British relationship with the Trucial States, as it sought to make them de facto colonies in the 15 years before the nation's formation. On a visit to the Trucial States at the time, Bahrain agricultural advisor Aubrey von Ollenbach proposed an agricultural research station as a solution that would have great benefits with only a modest investment of £25,000. It was a project for its age: modernism and science conquering the desert. At the same time, its budget was acceptable to a post-war British public weary of big schemes in the empire beyond its own shores.

At that time, the Trucial States were in the process of realigning from the Indian Ocean to Arab states. It was a period of economic change too. Agricultural production was for sustenance, not the marketplace; surpluses were sold or bartered.

Early on, British officials and technical experts legitimised the project on the grounds that the existing local economy was impoverished; its indigenous people did not know how to get the most out of the land.

At the time, Abu Dhabi political agent Archie Lamb described the local population as "ignorant, unemployed, unhealthy and ill-fed". The proposal followed famine in the 1940s and 1950s, and came at a time when many young men were leaving to seek employment in Kuwait. Science held the answers: fertilisers and water pumps would turn the desert into farmland and increase prosperity.

Oral histories, such as Honour is in Contentment by William and Fidelity Lancaster, belie these accounts: people here thought themselves self-sufficient.

Nevertheless, the British brought in Robin Huntington, a man whose charisma, fluency in Arabic and military experience in the Gulf made up for his lack of agricultural knowledge.

Huntington's job was to convince "local Arabs" that agriculture was a profitable commercial business and find out which crops he could grow commercially.

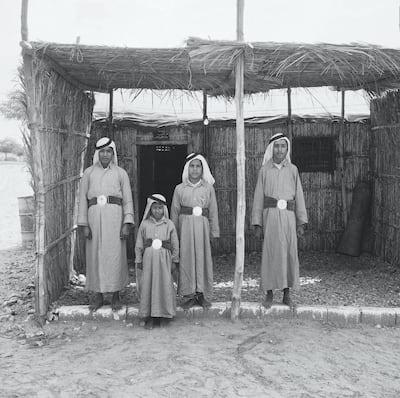

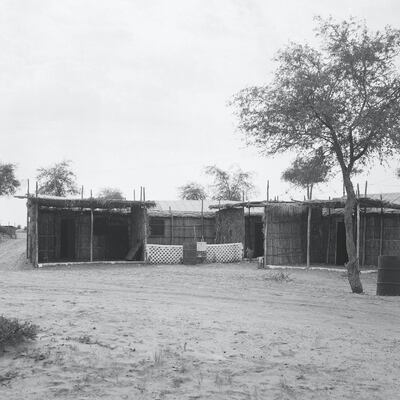

He made his home in Ras Al Khaimah, where he lived in a palm-frond hut, much to the embarrassment of his superiors. Known in Ras Al Khaimah to this day by his moniker Mansoor Al Britani, he was described as "the station's great strength and weakness in its early years".

Huntington and Von Ollenbach toured the north of the country in April 1955 searching for a suitable location, sending soil samples to Britain from Manama in southern Ras Al Khaimah, Digdagga and Nuwai, north-east of Buraimi, in what is now Oman. At that time, the Trucial States and northern Oman were still imagined as a one space, although this would fade in the 1950s and 1960s as the British worked to control the flow of weapons to the Omani interior.

Eventually, the unsettled, fertile plain of Digdagga was chosen for the Agricultural Trials Station. However, there was a reason for its availability: the soil was fertile but the land was empty as a result of being prone to destructive flash floods. Huntington immediately got to work. During the next few years, fertilisers, generators, mechanical and diesel water pumps, a well-drilling rig, bulls from Sindh and cattle from Kenya were imported, and experimentation with planting techniques began.

"They brought seeds from America," says Al Hebsi, who worked at the farm in those years. "Winter vegetable such as the radish – it's a beautiful colour – and the cabbage and the cauliflower. All of them were from America. They'd get the seeds and they'd try things out."

A 1961 visitor's report lists produce such as cabbage, cauliflower, tomatoes, beetroot and turnips, carrots, eggplants, gourds, onions, celery, cucumbers, lettuce, parsley, peppers, watermelons, radishes and cantaloupes.

______________

Read more:

The framers of Electra Street: the men who freeze moments from history

Inside the dhows of Abu Dhabi's Mina Zayed

‘Her name will live on in RAK for generations to come’

______________

Notable for its absence is the date palm. As Maclean writes: "The fact that British experts chose to focus on a wide variety of other crops to the exclusion of the date palm is instructive; in their ambition to create a modern economy, vestiges of 'tradition' had to be removed".

Tobacco, which had been grown for centuries, was also ignored as it was unpopular for export. "Huntington had planted tobacco in the spring of 1957, but about half of the seedlings were lost to insects on the first night," MacLean notes.

Huntington then founded one of the first modern schools in the Emirates, the Agricultural School. Eight boys registered in the first class. Al Hebsi enrolled in its second year in 1956, and studied "reading, writing and farming and the colours of the vegetables" under teachers from Sudan, Egypt, Palestine and Jordan. Pupils worked on the farm twice a day, morning and afternoon. After graduation, Al Hebsi stayed on at the school as a farmer until it was taken over by the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries in 1972, which he then joined. The first harvest of 1956 was a great success. There was just one problem: nobody wanted the "strange" vegetables.

Al Hebsi tells one story of when the first vegetables began to arrive to market. A man who bought a cabbage began to peel it, leaf by leaf, waiting to see what fruit was inside. He peeled off all the cabbage's layers, only to find it empty.

Al Hebsi remembers being told how to cook the vegetables and taught their nutritional value. Nonetheless, his classmates had a difficult time acquiring new tastes, much to the frustration of their Sudanese teachers. Mulukhiya from Sudan and bitter arugula, now a majlis favourite, were particularly hard to swallow. Yet tastes would change as men travelled abroad for work and ate in oil-company canteens.

When it came to selling the vegetables, the British were in a bind. Officials were not allowed to run for-profit enterprises, but without it, they couldn't show local farmers that commercial farming was viable.

It was agreed that Huntington would sell the vegetables to the Royal Air Force base in Sharjah, with all profits going to the Treasury.

Distribution was another challenge. Prices varied from one emirate to another, making it hard for traders to know whether it or not it was worth an arduous journey to Abu Dhabi or Dubai. This was resolved by proposing a radio broadcast announcing set prices.

"This is how nations form in other ways than having a political boundary; it's the information flow," MacLean says. "The same information is available to everyone within a space or within a given territory and the same opportunities are available to everyone."

"The idea that you should have a radio broadcast and sufficient roads and transportation so that goods get to different places and that the price should be uniform across the country – that's the beginning of the imagination of a national space.

"It's interesting in the same period when the British were defining boundaries between different Trucial States for oil exploration, they were also engaged in this agricultural project, which involved crossing boundaries.

"This is an old question in literature on capitalism: is capitalism about fixing places or about mobility? It's about both."

Irrigation also changed social interactions. Traditional aflaj water channels were abandoned in favour of using groundwater from wells, a recommendation by an agriculturalist from British Middle East Development Division, J C Eyre after a visit in 1957. In 1955, as many as 200 water pumps were in use across the Trucial States. By 1960, there were 1,000 in Ras Al Khaimah alone.

The distribution of pumps, seeds and mechanical equipment required closer integration with a modern capitalist economy. Farmers needed loans to buy pumps, and banks asked for farms as collateral. Suddenly, property deeds became of great importance in a region where none had existed.

When loans were secured, many struggled with the idea of scheduled payments, having previously relied on a system of honour.

Eyre's second recommendation was dam construction to hold back floodwaters so that more land could be cultivated. Much later, it would be discovered that floods were essential to maintaining the region's water tables.

Huntington left in 1961 and returned to Canada, where he had citizenship. His replacement was Ted Morgan, a Brit who came from Sudan and expanded the school to 70 students – 60 boys and 10 girls.

Morgan was succeeded by Robert McKay and his wife Margaret, who flew in the region's first herd of dairy cows from Britain in 1969. That year, RAK's expatriates enjoyed fresh milk in their tea for Christmas. It was the first time dairy cows had been known to survive in such heat.

At the time, the station was considered a success, although it's contribution to commercial

agricultural is hard to measure. "Events overtook it," as MacLean notes. The United Arab Emirates was formed in 1971 and oil wealth saw rapid urbanisation.

The Agricultural Trials Station is now on the grounds of the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change headquarters for the northern region, whose current director investigates organic farming and hydroponics. This is precisely the opposite of the station's earlier farming ambitions.

Huntington is still fondly remembered. Al Hebsi has in his possession a letter of recommendation that the stationmaster wrote, commending him for being "good-mannered, honest and industrious".

"I worked with them all," Al Hebsi says. He describes McKay in the most glowing terms as "a man higher than the mountains".

Yet the legacy of the station is in doubt. In the past 20 years, Al Hebsi's thousand palms have perished because of the drop in water tables. The water has become brackish. He has replanted another farm of 100 palms, maintained by 2,400 gallons of sweet water imported every week. Today, Digdagga has many orchards of dead palms. "Things just got weaker," he says. "The water is done – all the water that was good."

These days it seems, it is not to the future but to the methods of the past that farmers must look for answers.