In January 2014, most Iraq analysts knew security in the country was rapidly deteriorating. Beyond general warnings, however, few predicted exactly how bad the situation would become.

Within six months, a fanatical terrorist group in the form of ISIS would take over a third of the country, embarking on a brutal campaign of violence. By August, the UN declared Iraq a "level 3 emergency" (the worst kind) as 3 million people fled their homes.

But what if all of this could have been predicted far in advance? Not a general warning that things were getting worse, but rather a detailed prediction outlining the severity of potential conflict and the likely timeline.

Forecasting temporal and spatial aspects of conflict is now the task of researchers at the Turing Institute, the UK’s national institute for data science. It is a problem that has vexed political scientists for decades and to date, most efforts have only succeeded in very broad warnings, ranking states at risk of violent episodes occurring within around one year.

Unsurprisingly, this is because predicting conflict is immensely complex. There is an endless number of inputs for any model. Some analysts focus on environmental factors like drought and food security. Others look at political economy, the interplay of governance and living standards, to provide structural risk analysis.

Complicating this, the sum of data used must be reliable. But in many conflict-affected areas accurate data is hard to come by.

To wade through this maze of information, the Turing Institute has been harnessing artificial intelligence to give policymakers highly specific warnings. This is known as the Global Urban Analytics for Resilient Defence – or GUARD – project.

I asked Weisi Guo, the lead analyst on GUARD, why it is different from previous attempts to foresee conflict. According to Dr Guo, the strength of his institute’s approach involves boosting human analysis with computing power.

“Reasoning in conflict prediction is largely qualitative – involving arguments and debates – or quantitative – involving data and statistical regression (modelling with several variables). We boldly attempt to write logical equations that tie different factors together, and then apply AI to make data-driven predictions.”

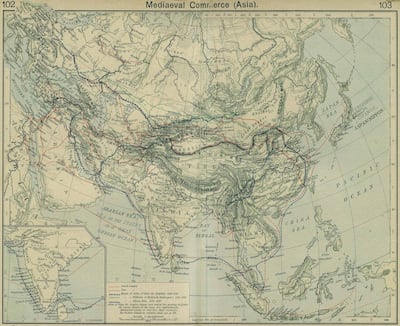

Behind Dr Guo’s vision is a realisation he made in 2015, when looking at a map of the ancient Silk Road. He was struck by how many of today's most severely conflict areas correspond with the historical web of trade routes that once connected East and West, passing through the Middle East. He then created an algorithm splicing publicly available databases on violent incidents with overland routes, placing physical geography at the heart of his research.

Dr Guo is keen to stress that land routes are not the only component of GUARD. But concentrating on historic “choke-points,” in the flow of goods and people has led his team to some remarkably accurate predictions. In 2017, they were able to predict 76 per cent of the cities in which terror attacks occurred.

Indeed, it is those “junction cities,” where most violence takes place. Mosul, for example, has historically held this status – the city’s name loosely translates as “junction” in English. The geography-violence nexus, Dr Guo emphasises, is particularly relevant in the Middle East.

“The Middle East is of course interesting and complex, more so than most places, because it sits at the heart of Eurasia, the super-continent of information, cultural, resources, and people flow, It is by far the most well-connected continent. Being in the middle means [the Middle East] receives a lot more attention, and we use graph theory along with AI to understand which parts of the region are more vulnerable under dynamic political and trade conditions.”

For millennia, the flat expanse of terrain in the vast Tigris and Euphrates river valleys that cross Iraq and Syria has been a blessing and a curse for its inhabitants. Flat terrain enabled rapid movement of goods, accelerating the development of some of the world’s earliest city settlements. These routes were coveted and contested, allowing rival groups to quickly move cavalry into enemy territory.

Dr Guo's focus on geography may hold weight in modern times, too. Eight hundred years after the Mongols ransacked Baghdad, ISIS’s fleets of Toyotas exploited flat terrain to attack cities from unpredictable approaches. Clearly, geography makes certain areas more prone to conflict, regardless of state borders.

“Our model really differentiates cities and regions from countries, so we definitely see certain parts of countries to be far more unstable than other parts,” says Dr Guo.

At Uppsala University, in Sweden, another project – the Violence Early-Warning System, or ViEWS – is under way to harness AI to predict war. Like GUARD, ViEWs works on the basis that without regional detail, models are of little use.

The project is described by its lead analyst, Professor Havard Hegre, as “an ensemble of constituent models”. It has had some early success, correctly predicting a high risk of violence in the Somali region of Ethiopia in July 2018 – within a month, gun battles erupted there between police and militias.

With so much data on potential conflict online, it seems only a matter of time before forecasting could be completely automated. But looking at various forecasting efforts, there is significant disagreement on the value of social media. This seems strange at first – after all, the Syrian conflict has been dubbed the first “smartphone war.”

This is not lost on Professor Hegre, who believes social media is an important input for modelling, but has clear limitations.

“We are working on a Twitter model, so we are trying to identify tweets that are geo-tagged and refer to events,” he remarks. But a significant problem is that social media content has to be verified. Automated programmes also struggle with “sentiment analysis”. For example, they may struggle to detect sarcasm.

“What is challenging is to include high quality reports," explains Professor Hegre. “The Twitter project is an attempt to identify the markers of the scale or anticipation of violence. But we are not sure how feasible it is. It is a fairly hard problem to work on.”

For Dr Guo, the important thing to note is that whatever the inputs in a model, AI will likely remain a force multiplier for human analysts, rather than a stand-in.

“Human beings are great at ingesting diverse data, experience and what other people summarise and articulating that in a reasoned manner," he says. "So I do not see AI replacing humans. Far from it. I see AI providing a nuanced surrogate to human reasoning, reducing personality bias, explaining to humans via explainable AI interfaces and helping them draw conclusions.”

The human challenge of foreseeing conflict brings us back to the central problem: if policy makers had a better grasp of the emerging disaster in Iraq, would it have changed their calculations?

Iraq expert Michael Knights is sceptical. A senior fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, he envisages a system that could have monitored locations of mobile phones of Iraqi forces in the years prior to the fall of Mosul. This tech “could easily have provided a much better intelligence picture of Iraqi forces melting away at the frontline as they contacted ISIS probes,” he says.

But would this have been game-changing in Washington?

“If such a system could predict systemic security collapse in northern Iraq in the second quarter of 2014, then-president Barack Obama's administration would still have had to face the unpalatable choice of re-joining the war he campaigned to get us out of.”

According to Jack Watling, a research fellow at Britain’s Royal United Services Institute, a better use of AI could be to rally analyst resources to troublesome places at the earliest stage of crisis.

“AI monitoring of incidents in fragile states, while imperfect, can flag up potential trouble spots and anomalies that human analysts might have missed. By flagging this to human operators, potential tipping points can be identified and more analysis resources can be mobilized for that area.”

Like Dr Knights, Dr Watling is keen to stress there will always be the challenge of finding political will and co-ordinating elements of government. Even the best predictions will be no silver bullet.

“A red light flashing on a computer program won't necessarily mobilise resources,” he cautions.

Professor Hegre agrees, and sees particular value in raising accountability for policymakers, especially if there are warnings of mass violence of the kind perpetrated by ISIS. “What we are doing in ViEWs will only complement things we observe. But this will be in the public domain and it will be harder for everyone to say, 'Well, we didn’t know what was going on,' if a major crisis occurs.'"

But in the end, what will matter above any calculation or warning from a machine is political will. And that quality, or a lack thereof, is all too human.

Robert Tollast is a security and political risk analyst focused on Iraq