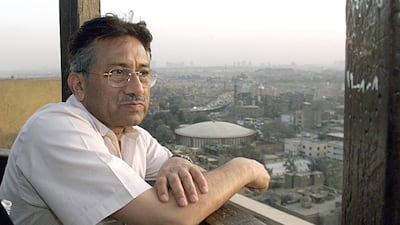

Syed Pervez Musharraf was born in Delhi in 1943, four years before the birth of Pakistan, the country he would eventually lead for nearly 10 years. He died in Dubai much like the way he was born, outside his homeland. Although highly polarising within Pakistan, he remains a major historical figure whose legacy continues to shape Pakistan and the region in many fundamental respects.

Born into a family with a long bureaucratic lineage, it was always more likely than not that he, too, would enter public service. But unlike his forebears, he chose the Pakistan Army. Entering the military academy at Kakul in 1961, his life as cadet, soldier and veteran spanned across two thirds of the Pakistan Army’s existence.

This is the institution on which he had the greatest impact and which, in turn, did the most to shape him.

Thanks to the coup that he led against then prime minister Nawaz Sharif in 1999, he served as the Chief of Army Staff (COAS) for nine long and tumultuous years. Largely driven by the need to rebuild a close alliance with the US following the 9/11 attacks, his tenure represented a decisive break with the Islamist ideology of Gen Zia ul Haq, a former army general who ruled Pakistan from 1977 to 1988.

Certainly, Gen Musharraf projected a very different kind of image from Gen Zia’s conspicuous public piety. Instead Gen Musharraf was comfortable posing for portraits with his unveiled wife, pet dogs and cigars. At the same time, he saw no contradiction between his lifestyle and his faith. This was very much the culture of the pre-Zia officer corps, until defeat and disgrace in Bangladesh in 1971 led to an upsurge of “born-again” religiosity.

In order to avoid being targeted for overthrow in the same manner as the Afghan Taliban, Gen Musharraf from 2001 onwards, instead, supported covert US efforts to capture and kill foreign fighters on Pakistani soil through everything from CIA special forces raids to drone strikes. Soon, Pakistan was forced to wage an increasingly intense counter-insurgency against radical homegrown and emigre extremist forces on its own soil. All of this soon led to assassination threats against Gen Musharraf from extremists as well as many cases of outright desertion and mutiny by sympathisers within the Pakistani armed forces.

In order to justify his highly pragmatic and adaptive policies, Gen Musharraf was forced to break with Gen Zia’s radicalising claim that the Pakistani uniformed services were the sword arm of Islam itself. Instead, the army’s job was to defend Pakistan’s national interests, as understood in largely secular terms. This did not stop the army from utilising alliances with religious militants where they proved useful, but it also allowed it to avoid being trapped by the ideological rhetoric and sacrifice its militant alliances whenever their utility declined.

Gen Musharraf, for example, did not hesitate to betray his longstanding allies in the Taliban to the US in 2001. His decision to renew support to the Taliban in 2004 and anger his American friends was not the result of anti-Americanism or affinity with Islamism. Instead, it came from a determination to prevent India from expanding its influence in Afghanistan, as well as deep anxiety over the growing Baluch insurgency on the Afghan-Pakistani-Iranian border. This approach is still alive and well – at present, the army appears to be preparing to punish the Taliban for dallying with India.

This cynicism has destroyed the close alliance with the US, and may yet do so with the Taliban as well. But this highly nationalistic agnosticism has been a lasting change that has allowed the military and Pakistani state to survive stresses that have threatened the governments of some other Muslim states.

Even more significantly, Gen Musharraf succeeded in building institutional safeguards strong enough to avoid the long-feared nightmare scenario of extremist militants inside or outside the military gaining control over Pakistan’s rapidly expanding nuclear arsenal. For this, if nothing else, the world owes him enduring gratitude.

None of these changes should be seen as inevitable; in the first few years of his tenure, Gen Musharraf took extraordinary risks, whether provoking India through various kinds of campaigns or shielding the global nuclear technology proliferation network led by AQ Khan.

But it is just as clear that his almost-compulsive propensity for risk-taking shifted from his policies outside Pakistan to those within it. His larger goals for Pakistan seemed to shift from deterring and punishing its adversaries through security means to modernisation and economic growth. The satellite television revolution, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, the Higher Education Commission and a renewed emphasis on entrepreneurship all owe their existence to Musharraf-era initiatives.

Unfortunately, Gen Musharraf’s results after attempting to re-jigger Pakistan’s national ideological foundations were far more mixed than his efforts inside the army. Certainly the country’s secular educational infrastructure expanded its private electronic media ecosystem and the culture of entrepreneurship has bloomed.

But meanwhile, government efforts to regulate extremist religious schools failed. And constant and unaccountable military meddling meant democratic activists were more likely to experience intimidation than anti-state extremists. The result has been that a highly inflammatory and populist approach to religion has thrived. Anti-blasphemy vigilantism and social polarisation as a result has grown steadily worse in the years since.

This schizophrenic combination has produced an increasingly tech-savvy population, but also a government machinery that has often put more effort into expanding religious censorship on the Internet than supporting innovation.

Gen Musharraf was forced to surrender the post of COAS and his uniform in 2007, and his post as president in 2008 after having incurred the wrath of the Americans on the one hand, and Pakistan’s powerful judiciary and bar associations on the other.

His decade and a half in retirement (largely in exile) since then has been punctuated by civilian attempts to punish him for his acts as leader, and failed attempts to break once again into national politics. The former thanks to zealous military protection and the latter due to strong civil opposition for his myriad sins as a dictator.

This “hybrid” civil-military stalemate is itself a reflection of Gen Musharraf’s mixed legacy as a soldier and statesman. Despite the troubled relationship with the man, in life and now his death, the country remains Gen Musharraf’s Pakistan.