They are hard to find and blend in to the Paris suburbs usually avoided by tourists, amid rows of high-rise buildings and fast-food shops that smell of fried chicken or industrial areas populated with car repair shops and wastelands.

Where exactly the homeless migrants moved by the state outside of Paris during the Olympic and Paralympic Games live is a closely guarded secret, but The National found some in hotels with faded signs or abandoned hospitals far from the heart of the action.

Their fate post-September 8, when the competition winds up, is an open question as activists probe the state about the social legacy of the Olympic Games. There are fears they will be sent back to the street and have accused the state of deliberate opacity regarding their fate.

Many describe dirty kitchens and a lack of intimacy but are typically grateful for having a roof above their head and a bed to sleep in.

professor of political science at Pacific University in Oregon

“We moved here just before the Olympic Games, but life was better at the previous hotel. It was a real hotel. It was clean. Now we share a kitchen and it's a bit dirty,” said a teenage girl and her twin, who were staying with their mother in a hotel in the suburb of Gennevilliers.

They said they came from Ivory Coast and had lived in the streets after a dispute between their parents before they were offered a spot in a hotel last year. Lots of people have been arriving in their new hotel in the past weeks, they added.

What will happen when this temporary arrangement is wound up? The girls had no idea.

No one else knows, except for the state agency that oversees these shelters, or prefecture. It didn't answer The National's repeated requests for comment. The non-governmental organisations that run them on a daily basis on behalf of the prefecture also didn't answer requests to visit the shelters.

Deliberate opacity

The state has in the past rejected claims by activists that linked it moving homeless people living in Paris to faraway cities or suburbs to the Olympic Games.

“Not true,” Ile-de-France region prefect Marc Guillaume told national media when asked about accusations of “social cleansing.” The prefecture has instead highlighted a flagship programme to move 216 homeless people who used to live near Olympic sites out of the street to long-term accommodation.

Yet the numbers of people expelled from slums, squats and informal tent settlements dramatically rose ahead of the sporting event, reaching 12,500 between April 2023 and May 2024, a 38 per cent increase compared to the previous year, according to activists from a coalition of NGOs called Le Revers de la Medaille.

Some NGO staff working in these shelters, who asked to not be named because of the sensitivity of the subject, said there was a clear link between the recent arrivals in their shelters and the Olympic Games. “But to us, it doesn't matter. Our job is just to help them,” said one.

Lea Filoche, deputy mayor of Paris in charge of emergency accommodation and refugee protection, told The National that she was “very worried about what will happen in September”.

“I don't think the shelters given to people near Paris during the month of July are long term. I think these people will be put back on the street,” she said.

The spokesman for Le Revers de la Medaille, Antoine de Clerck, was even more adamant than Ms Filoche. “I'm 99 per cent sure these people will be back in the street in September,” he said. “The whole system is made to be opaque on purpose.”

Bussing people out of Paris is a practice that predates the Olympic Games. It goes back to February 2023, as the arrival of migrants gradually increased after the pandemic lockdowns, according to Ms Filoche.

There are worries this will create a boomerang effect – instead of reducing the presence of homeless people in the streets of Paris, it may exacerbate the issue on the long term.

Ms Filoche, a left-wing politician opposed to the current government's migration policy, said she believed their number was currently more than 5,000. It's more than the almost 3,500 accounted for during a yearly count in January, but Ms Filoche said she believes “at least 50 per cent” manage to hide from the city's services. The January 2024 figure was 15 per cent higher than the previous year.

“The Olympics are an inequality machine: they tend to intensify the social problems that already exist in the Olympic city,” said Jules Boykoff, professor of political science at Pacific University in Oregon and the author of six books on the Olympic Games. “So, in Paris, the Olympics certainly didn’t cause the issue of homelessness, but it intensified the situation and galvanised an intensified response.”

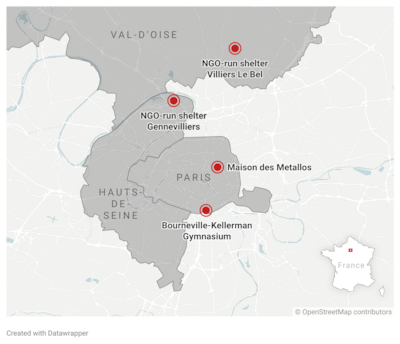

A number of media reported on homeless migrants being bused out of Paris to cities such as Marseille or Orleans earlier in the year, but it appears that in June, the state decided to open emergency shelters closer to Paris.

Nearly 600 spots were opened in “buffer sites” by early July, an internal document of the regional state housing management institution viewed by The National shows.

“Strategically, it makes sense,” said Melora Koepke, a Canadian urban geographer based in Paris. “Let's get as many people out as possible while saying there's no alternative, then those who don't go will be given a spot at the last minute.”

Yet finding their exact location was often impossible because of lack of detail.

Some shelters did not appear on the websites of the NGOs managing them. When asked for a press visit, they said they would examine the request but did not provide a response by the time this article went to print.

From airport to former hospital

At Villiers-Le-Bel, a town north of Paris that was the flashpoint for anti-police riots in 2007, 150 homeless people were housed in a former hospital in the weeks before the start of the Games. Managed by NGO France Horizon, the three-floor building also hosts refugees and asylum seekers with their families. Part of it will soon be demolished.

France Horizon said it aimed to support the homeless who had arrived at the shelter ahead of the Games with basic needs and direct them towards longer-term shelters. They were identified by the Red Cross at Charles de Gaulle Airport.

“Like many associations, we often set up accommodation centres in unoccupied buildings [former hospitals, former schools, former offices] that are ultimately destined for rehabilitation or demolition,” a spokesman said. “In a context of housing crisis and real estate tensions, this is often the only way we have to allow people in need to avoid living on the streets.”

The arrival of homeless people appears to have been done without informing local authorities. The mayor of Villiers-Le Bel, Jean-Louis Marsac, told The National he was unaware of their presence, and that the prefecture was supposed to warn him of new arrivals but had not done so.

Cities routinely complain that they have to carry the burden of caring for the homeless despite it being a state responsibility. The issue is particularly acute in Paris, where most newly arrived immigrants head first when they arrive in France.

“I've been working on this for four years, and for four years, we've been in great difficulty. We need to legalise undocumented migrants to free space in shelters,” said Ms Filoche.

One particular blind spot in the judicial system is the case of isolated minors waiting for the state to recognise that they are under 18, so that they can be given shelter instead of living in the streets.

Many of them used to squat a city-owned cultural venue named the Maison des Metallos in the north-east of Paris. They moved in early July after discussions with the city hall to gymnasiums. Before they left, the residents had put up banners that read: “no accommodation, no Olympic Games. We stay in Paris.”

Exceptionally, they were allowed to stay in the gyms 24 hours a day, instead of only at night, to avoid risks of being arrested during the day due to increased police presence, said Ms Filoche. The city has been housing isolated minors in gymnasiums on a rotating three-week basis since December, she added, as arrivals increased.

The gymnasiums are populated mostly with young men from West Africa, who sleep with little privacy on camp beds in what was built to be an indoor basketball court.

They busy themselves going to French classes given by NGOs and have created a makeshift praying area in the centre of the hall.

Kaba, 15, who currently lives in Bourneville-Kellerman gymnasium in southern Paris, spoke shyly of his eight-month journey with a cousin by land and by sea from his native Guinea to Italy in search of a better life. He then travelled onwards to France alone. In Paris, he slept in the streets until he heard of the gymnasiums through acquaintances.

“Life is OK – kind of,” he said. “I hadn't imagined this kind of suffering before I left home.”

Kaba keenly awaits to be confirmed in his status as a minor – a procedure that involves interviews with state officials – and be offered long-term housing. One day, he wants to be a car mechanic.

Outside the gym, dozens of young men and teenage boys played basketball with teenagers from the neighbourhood. Social differences disappeared as they dribbled the ball and competed to score the most points. They seemed mostly unaware that their fellow players lived inside the gymnasium.

That's how Nasiru, 16, from Gambia, made friends with Felix, Jules and Noam.

“Living here is really noisy,” said the former Maison des Metallos resident. “There's those that want to listen to music and talk loudly and those who want to rest.”

His former squat has now been turned into an upscale venue showcasing Tokyo as a tourist destination, according to Mr Boykoff. During a visit, he asked a Japanese host if she knew the building had used to house migrants. “I’ve heard,” she told him. “But I didn’t see them.”