It is often said that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, but deciding whether a camel is good looking is down to more than personal preference.

Camel beauty contests involve a complex, structured system of judging, which is just as well, because the stakes are high.

For example, at Al Dhafra Festival, held late last year near Madinat Zayed, the prize fund was well over $10 million (Dh36.7m).

The most attractive animals won their owners brand-new SUVs, while the value of these winning creatures increased. But competition is strong, with about 15,000 camels entered into the various categories.

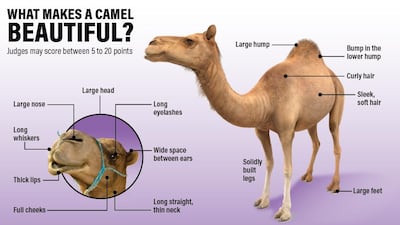

In a camel beauty contest or mazayna, animals are marked out of 100, and top animals can achieve scores reaching into the high 90s.

____________

Read more

Meet Batoola the camel, champion by name and by nature

Long legs and a shapely hump: how to spot a beautiful camel

____________

Overall appearance accounts for 30 points, with the animal’s coat – it should be shiny – along with general fitness among the factors looked at.

A further 20 marks are on offer for how the upper body looks, with a large hump that sits in the lower back ideal. The head and neck, the front of the animal and its rear are worth up to 25, 15 and 10 points respectively.

Whether such analysis is art or science is a matter for debate, but researchers are currently embarked on a project that they hope will bring additional scientific rigour to the field.

Dr Jaime Gongora, an associate professor in wildlife and animal genetics and genomics at The University of Sydney, and his PhD student Mahmood Al Amri are developing an exhaustive scorecard for camel beauty contests.

The work will focus on camel beauty contests in Mr Al Amri’s home country of Oman, where he holds a senior role in the veterinary services directorate of the royal courts, but the results are likely to be applicable more widely.

The scorecard will look at morphometric measurements, which are those that relate to the shape and dimensions of the parts of a camel’s body assessed during judging.

“This will help to enhance the traditional scoring system into numerical data using information collected from traditional assessment,” said Dr Gongora, whose other research projects take in creatures as diverse as the crocodile, platypus, oryx and peccary.

“We will validate the efficacy of the numerical scoring card we have developed to assess its consistency with the judges’ decisions in ranking those camels during the beauty competition seasons in Oman.”

The project will allow for “a more transparent process in making decisions”, helping everyone from contest organisers to camel owners and competition judges.

Linked to the development of the scorecard will be genetic studies of the camels, allowing the researchers to carry out an “association analysis” between the physical, or phenotypic, traits of individuals, and their genetic makeup.

There are no plans to use this information to recommend selection or breeding strategies for show camels, but this type of knowledge is often taken advantage of for such purposes.

The understanding of how genetic markers relate to traits is less detailed in camels than in some other domestic animals such as cattle or sheep.

Dr Pablo Orozco-terWengel, a lecturer at Cardiff University in the UK, estimates there are just a few per cent as many markers in camels. With sheep, cattle or pigs, a single analysis may involve hundreds of thousands or even a million markers.

The acute disparity between camels and some other domestic animals may not last, however.

“You don’t have as much stuff with camels yet, but I foresee that will change in the future, especially as people become more interested in camels,” he said, with this interest growing because of climate change.

“They can cope with very extreme environments, very hot, very dry … [that] many other species cannot deal with properly. So they’re very interesting from that perspective.”

A study published by Dr Orozco-terWengel and colleagues in 2016 used genetic analysis to indicate that the domestication of the dromedary, which has the Latin name of Camelus dromedarius, took place in what is now the UAE and Oman.

Early genetic studies looking at proteins in camels, from the 1990s, found there was little variation or polymorphism. This research involved electrophoresis, in which the proteins move in an electric field.

Improved technology involving DNA has since been much more effective at showing variation.

Two main types of markers are typically looked at. There are microsatellites, which are sections of repeated DNA sequences that vary from one animal to the next. Also analysed are Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) markers, in which random sequences of DNA are used for comparison.

As an example, a 2011 study on camel breeds in Egypt used microsatellites and RAPD markers to identify variation between camel breeds.

Although camels are relatively poorly characterised in terms of genetic markers, there is even less known genetically about South American members of the same family of animals, the Camelidae, such as llamas and alpacas.

“For the South American camelids, we only have a handful of markers,” said Dr Orozco-terWengel, adding that scientists were now “taking the first steps” to generating genetic data for them.

Advances in technology and associated reductions in cost mean that many more markers are likely to be available in future for both South American camelids, as well as for camels themselves.

When it comes to the research being carried out by Dr Gongora and Mr Al Amri, however, the first priority is to develop the scorecard and, after that, to look for associations between genetic factors and physical characteristics.

The Middle East is currently enjoying another camel beauty pageant, the King Abdulaziz Camel Festival in Saudi Arabia, which runs until February 1. No doubt many of those attending and showing off their prized animals will be interested to learn more about the results of Dr Jaime and Mr Al Amri’s research, when they are finally released.