The recent Cop27 summit in Egypt highlighted the difficulties the world has in dealing with what is increasingly being described as a climate emergency.

While agreement was struck on financial assistance to help poorer nations deal with the effects of climate change, there was concern about the lack of progress in limiting greenhouse gas emissions.

The world’s continuing struggles to get a grip on climate change ― just as its effects become increasingly apparent ― is a stark contrast to the action taken to protect the ozone layer.

This protective shield in the stratosphere (the area of the atmosphere above the troposphere, which stretches up 12 kilometres from ground level) filters the sun’s ultraviolet rays, but a hole over the Antarctic became evident in the early 1980s.

January 1 marks the anniversary of the coming into force, in 1989, of the Montreal Protocol, the universally ratified treaty that provided a framework to significantly cut the release of ozone-depleting substances. The protocol has had a transformative effect.

"I think it’s been massively effective. It’s been a huge success," says John Pyle, co-chair of the protocol’s scientific assessment panel.

"It’s well documented that when Kofi Annan was secretary general of the United Nations, he called it the most successful environmental treaty ever."

Indeed, the protocol is now credited with the phasing out of more than 98 per cent of substances, such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), that harm the ozone layer.

Such has been the protocol’s impact that scientists predict that by about 2060 or 2070 the ozone layer will be close to the levels it was at decades ago. Changes in the atmosphere linked to global warming will prevent the ozone layer from completely returning to its former state.

The rise of climate change scepticism

Several factors made the ozone layer issue easier to deal with than climate change.

One, Mr Pyle says, is that the scientific evidence over the damage to the ozone layer was more clear cut and so received rapid acceptance, even from the very industries that produced ozone-depleting substances.

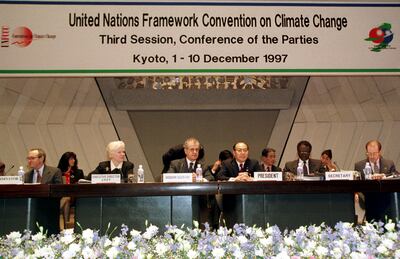

By contrast, when the Kyoto Protocol — the treaty that aimed to reduce the release of greenhouse gases — was agreed in the 1990s, there was much scepticism that human activity was even causing climate change.

"There were a very large number of people … you could call them climate change deniers, who didn’t think there was a problem," says Mr Pyle, an emeritus fellow at St Catharine’s College, part of the University of Cambridge.

While there is now much wider acceptance of the scientific evidence related to climate change, Mr Pyle says this has taken longer than was the case with the ozone layer.

The dangers from climate change, even when accepted, may have lacked the immediacy of the fact that the ozone layer was damaged and people were at increased risk of skin cancer and cataracts because sunlight was not being filtered as it should have been.

"With climate, a lot of the risks were uncertain and in the future," says Bob Ward, policy and communications director of the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, part of the London School of Economics.

"For a long period people felt we had more time and it wasn’t clear we needed to act as strongly. Unfortunately, all that was wrong."

The actions required to deal with the damage to the ozone layer were less difficult to bring about. Products that damage the ozone layer had a more select range of uses, such as in aerosols and refrigerants, and alternatives were available.

Indeed, says Niklas Hoehne, founder of the NewClimate Institute for Climate Policy and Global Sustainability, a think tank in Germany, many of the companies that produced ozone-depleting substances also manufactured the alternatives, so there were fewer vested interests to come up against.

"For climate, it’s very different. The companies that do business with fossil fuels, they go out of business," Mr Hoehne says.

Burning fossil fuels is central to so many activities of modern life, from generating power to travelling by land, sea or air, so stopping the production of greenhouse gases requires an almost wholescale transformation of economies.

Aid for climate strategy

Another factor in favour of dealing with the depletion of the ozone layer is, Mr Hoehne says, that the financial mechanisms to reward developing nations for moving away from the use of harmful substances worked well.

The Multilateral Fund for the Implementation of the Montreal Protocol, set up in 1991, has offered money and technical assistance to help developing nations move away from the use of ozone-depleting substances. It has, the UN Environment Programme says, put more than $3.9 billion into more than 8,600 schemes.

"Developed countries paid money into a fund. That’s a success," Mr Hoehne says. "But it’s a much smaller scale. With climate we need an order of magnitude [greater] to solve that problem. That’s difficult."

While the Montreal Protocol is widely hailed as a success, its implementation has not always been plain sailing.

In its initial form, Mr Pyle says, the protocol would not have prevented the atmospheric concentration of ozone-depleting substances from increasing, but would have slowed its growth.

The protocol’s strengthening over time has ensured that their concentration is now falling, which has allowed the ozone layer to begin to recover.

Yet a number of years ago the panel that Mr Pyle co-chairs identified that concentrations of some harmful substances were not declining as they should have been.

"It was realised that production and emission of these gases was occurring in the Far East, which was essentially against the protocol," he says.

"That’s now stopped. The fact of having regular scientific updates means we can keep track of what’s going on … I think what we cannot afford to be is complacent … but we’re in a much better place than we would’ve been."

Limiting global warming

With climate change, the forecast is that temperatures will have risen 1.5ºC above pre-industrial levels within a decade.

Yet, far from carbon emissions being cut in the way that scientists have said is necessary to prevent the worst effects of climate change, in 2022 they are expected to reach a record 37.5 billion tonnes, it was announced at Cop27.

Analysts do, however, see cause for optimism. The increasing adoption of renewable energy, such as wind and solar, moves the possibility of net-zero economies closer.

"We know we can use renewables at large scale to replace gas and coal to generate electricity, and electric cars instead of petrol-driven cars," Mr Ward says.

"These technologies have come on. But there are still areas where we find it more difficult and this is against the background of the risks growing."

Some of the fields where decarbonisation has proved harder include cement and steel production, Mr Hoehne says, but even here there are signs of transition, such as the emergence of "green steel", where the energy required is provided by hydrogen.

"For steel the alternative has to be provided by the same companies, so steel companies are not under threat of losing their business model. They ‘only’ have to change their production processes, but they still have a role in the market," he says.

So, although net zero is still at least decades away, the fight against climate change is making technological progress. Yet it remains a much tougher challenge to solve.